As a recent blog post explored, DeFi – decentralised finance – can and will be used in whatever ways developers and the market see fit. This is the nature of open, decentralised systems. You can’t stop it, and there’s a very strong argument for saying we shouldn’t try. To restrict any element of DeFi, at least at the protocol level, is to introduce centralisation and single points of failure, thereby killing the core innovation by misguidedly trying to protect it.

But “decentralisation” is widely misunderstood. It is, first of all, not a binary matter: a project is not either “decentralised” or “centralised”. Decentralisation lies on a spectrum. One node in a blockchain “network” is centralised; Bitcoin, with many thousands of nodes in its network, is typically considered decentralised. At what point does the threshold between centralised and decentralised lie? 10, 100, 1,000 nodes?

Secondly, there are different types of decentralisation. A blockchain network might be decentralised, but its mining infrastructure may not be, especially if a few pools comprise 51% of hashrate. If there are very few exchanges, or active developers, these are also forms of centralisation and points of potential vulnerability.

DeFi’s recent failings of decentralisation

We have seen other forms of centralisation and failure in the DeFi space in recent weeks, suggesting that a significant proportion of DeFi cannot truly be considered Decentralised at all.

At least two recent DeFi projects (one a fork of the other, and clearly designed to appeal to yield farmers, with improbable gains promised), include an “infinite mint” function that poise the devs to carry out an exit scam, pulling the rug from under holders when it is most lucrative (if not timelocked). SushiSwap, a now-notorious clone of UniSwap, apparently suffered a similar exit scam when its founder Chef Nomi took $14 million from the dev fund – only to return it in what may have been genuine remorse, or possibly an act of theatre.

Many of the ‘new’ DeFi protocols are simply clones of existing dApps, making them akin to a Ponzi or HYIP scheme. It’s worse when the users, who pour millions of dollars into these smart contracts, don’t wait for an audit – as was the case with Yam Finance, which led to a bug that caused its token price to crash to zero.

The ruthless elimination of centralisation

DeFi is not DeFi when it contains any of the above single points of failure. “Decentralisation” is about far more than the blockchain. Using a blockchain and smart contracts is an entry-level requirement for DeFi: necessary but not sufficient.

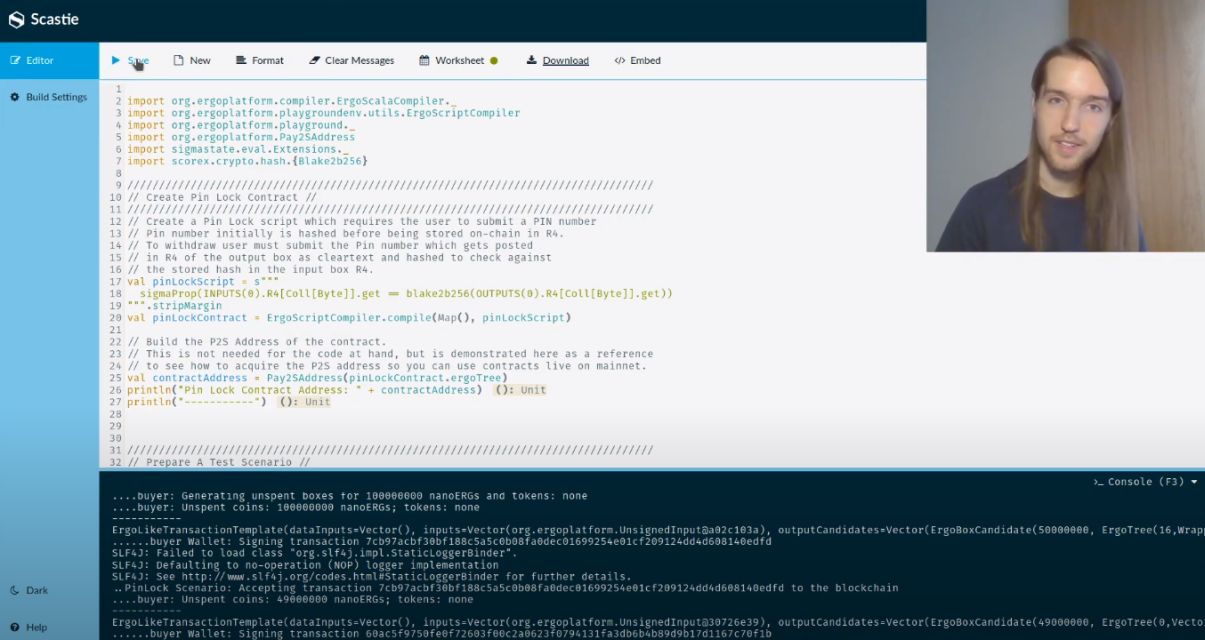

No protocol can be considered decentralised if it includes back doors, whether built in deliberately like the “infinite mint” function (Yuno), or that exist inadvertently, like the rebase bug in Yam Finance. They’re not decentralised if individual developers or small groups control large amounts of funds, the theft of which will destroy the project.

Adequate decentralisation from the outset may be impossible, but what matters is that unnecessary centralisation – in all its forms – is eliminated as soon as possible.

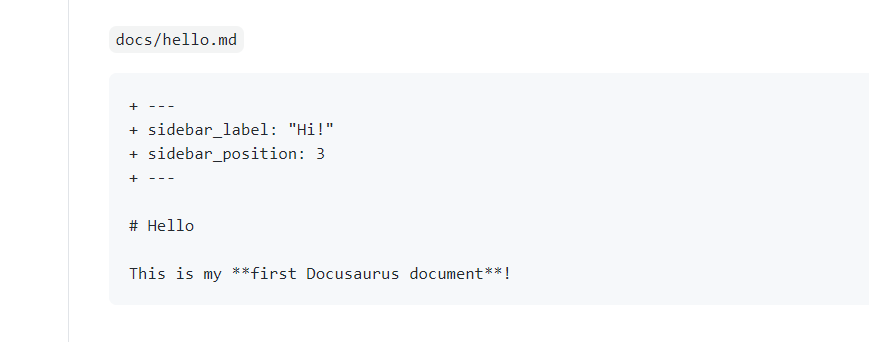

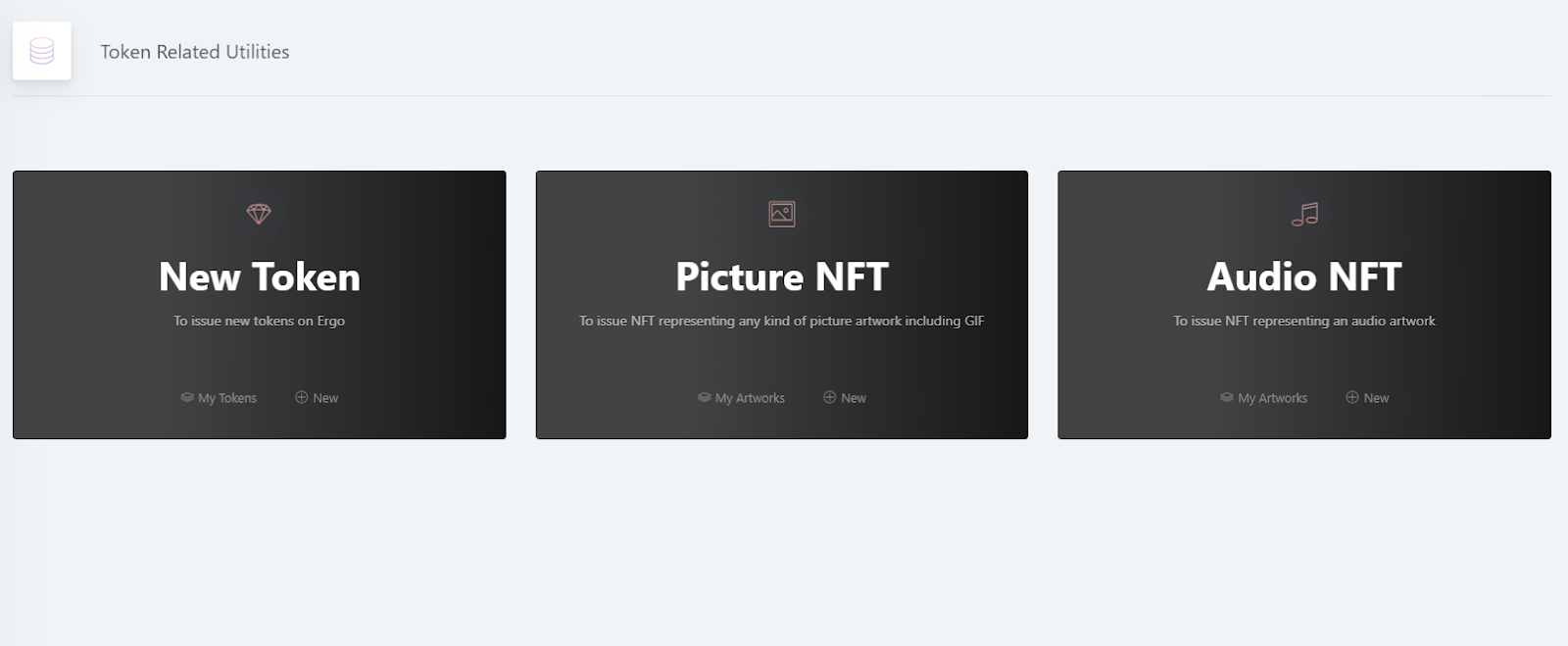

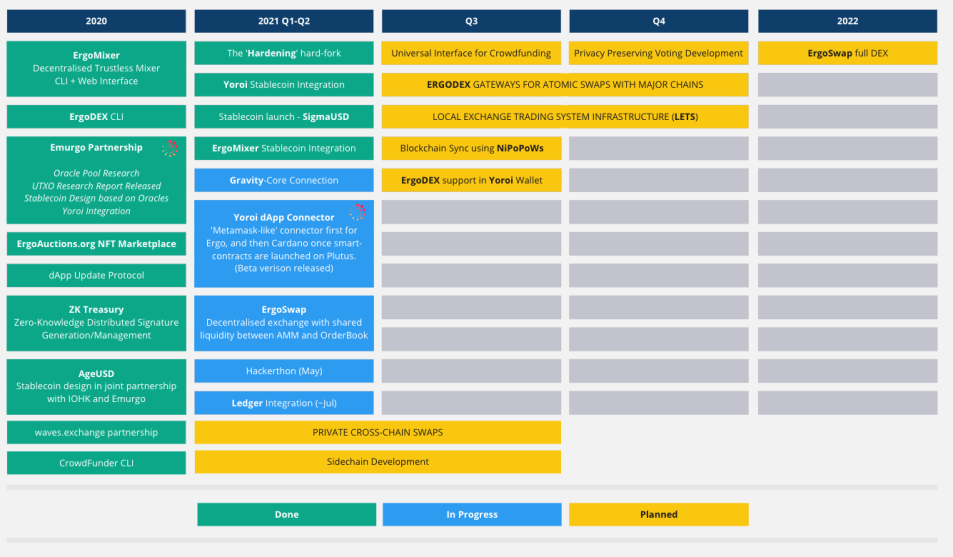

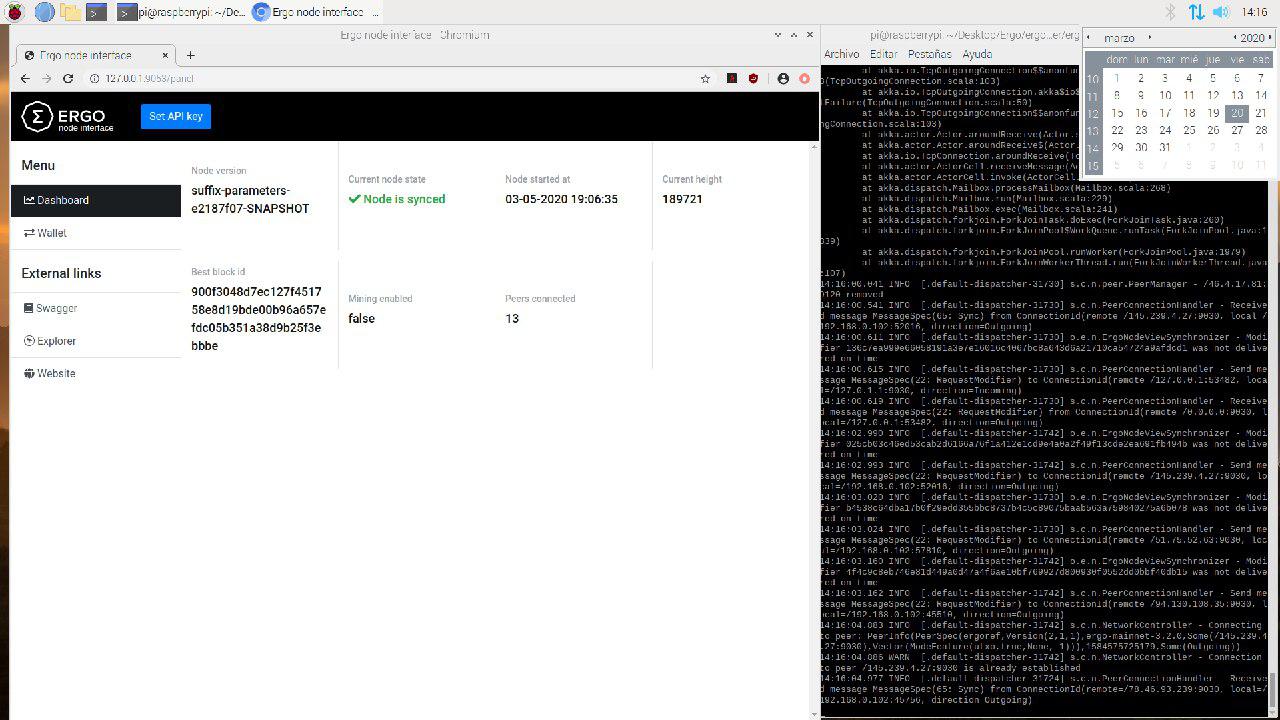

This is what Ergo is seeking to do: Building decentralised applications on decentralised blockchain infrastructure, with a strong and independent community of developers, smart contracts that are safe to run and easy to audit, and using custom joint signatures to protect community-owned funds.

To find out more, join the Ergo Discord or Telegram group.