This article describes a full featured ICO (Initial Coin Offering) implemented in ErgoScript. The example covers several important and novel features of the Ergo Platform and shows how it can support complex contracts with tiny amount of code.

Part 1. Preliminaries

An important design decision in a cryptocurrency protocol is specifying what a spending transaction actually spends. There are two possibilities here. The first a UTXO-based model, as in Bitcoin, where a transaction spends one-time asset containers (called as ‘coins’ or UTXOs in Bitcoin) and creates new ones. The other is an account-based model, as in Nxt, Ethereum or Waves, where a transaction transfers some amount of asset from an existing long-living account to another, possibly new, long-living account, with possible side-effects on the way, such as contract execution in Waves or Ethereum. In this regard, Ergo is similar to Bitcoin, because it uses the UTXO-based approach, where one-time containers called boxes are being spent. Interestingly, an Ergo transaction can also have data-inputs which are not being spent, but rather used to provide some information from the current set of unspent boxes.

It is not trivial to create an ICO on top of an UTXO based model, because, in contrast to account-based models, there is no explicit persistent storage here. However, Ergo brings a spending transaction into the execution context of a script. With this small change it becomes possible to express dependencies between transaction outputs and inputs. In turn, by setting dependencies we can execute even arbitrarily complex Turing-complete programs on top of blockchain (see the “Self-reproducing Coins as Universal Turing Machine” paper). In this article we will define a concrete scenario of a multi-stage contract using an ICO, where we have three stages (funding, token issuance, withdrawal).

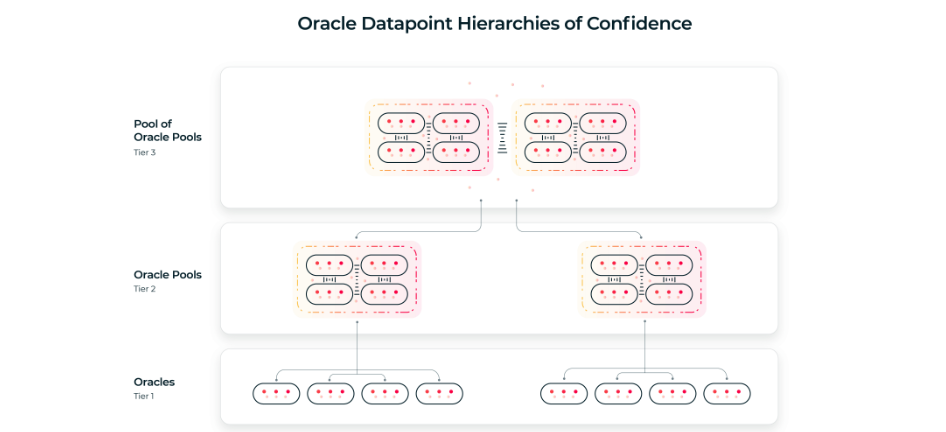

Now imagine an ICO for thousands of participants. Unlike Ethereum, Ergo does not provide possibility to store large sets of data and carry them over throughout contract execution. Rather, it allows to store only about 40-bytes header of a data structure, represented as key -> value dictionary, authenticated similarly to Merkle tree. To access some elements in the dictionary, or to modify it, a spending transaction which is triggering protecting script execution should provide lookup or modification proofs. This gives possibility for a contract to authenticate potentially huge datasets without requiring much memory to store contract state. However, storing space in the state (of active contracts) would mean bigger transactions, but this problem is easier from scalability point of view, and scalability is a top priority for Ergo.

Part 2. The ICO Contract

There could be many possible scenarios associated with an Initial Coin Offering (ICO). In this article we consider an ICO that wants to collect at least a certain amount of funds (in Ergs) to start the project. Once the funding threshold is crossed and funding period ends, the project is kickstarted and ICO tokens are issued by the project based on the total funding collected. In the withdraw phase, which extends forever, the investors withdraw ICO tokens based on the amount they had invested during the funding period. The contract steps are briefly described below with details provided further:

- First, funding epoch takes place. It starts with a project’s box authenticating an empty dictionary. The dictionary is intended for holding (investor, balance) pairs, where investor is a script protecting the box containing withdrawn tokens. For the balance, we assume that 1 token is equal to 1 Ergo during the ICO. During the funding epoch, it is only possible to put Ergs into the project’s box. A funding transaction spends the project’s box and creates a new project box with updated information. For that, a spending transaction for the project’s box also has other inputs which hold investor withdrawing scripts. Investor scripts and input values should be added to the tree of the new box. There could be many chained funding transactions.

- Second, the funding period finishes, after which the tree holding the investors data becomes read-only. An authenticated tree could have different modification operations allowed individually: inserts, deletes, updates, or all the operations could be disallowed (so the tree could be in the read-only mode). Also, this transaction creates tokens of the ICO project which will be withdrawn in the next stage. The project can withdraw Ergs at this stage.

- Third, investors withdraw their ICO tokens. For that, a spending transaction creates outputs with guarding conditions and token values taken from the tree. The withdrawn pairs are also cleared from the tree. There could be many chained spending transactions.

These three stages should be linked together in the logical order. A seqience of boxes are used to achieve these goals.

Part 3. The ICO Contract Details

Now it is the time to provide details and ErgoScript code of the ICO contract stages.

The Funding Stage

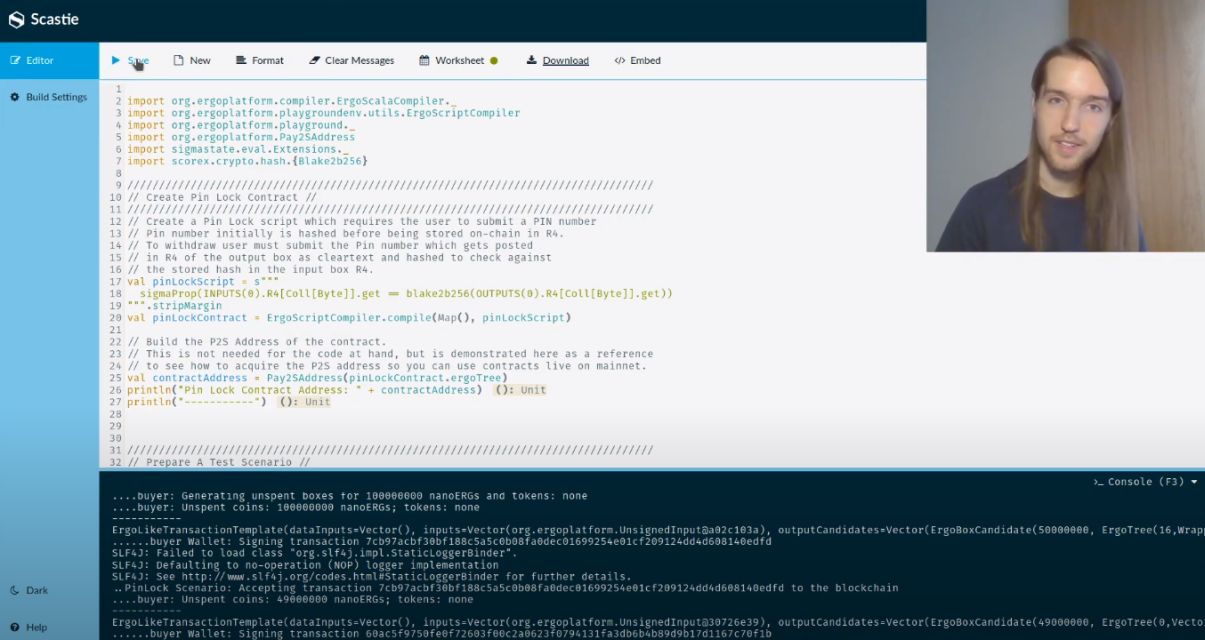

In the funding stage, which comes first, we assume that initially a project creates a box committing to an empty dictionary (stored in the register R5) with some guarding script described below. This stage lasts at least till height 2,000. More concretely, the first transaction with height of 2,000 or more should change the output box’s script as described in the next section (transactions at lower heights must output a box with the same script).

The project’s box checks that it is always first input and output of a transaction. The other inputs are considered investors' inputs. An investor’s input contains the hash of a script in register R4. This hash represents the withdraw script that will be used later on in the withdraw phase. The hashes as well as the monetary values of all investing inputs should be added to the dictionary. The spending transaction provides a proof that investor data are indeed added to the dictionary, and the proof is checked in the contract.

It is not checked in the funding sub-contract that the dictionary allows only insertions, and not updating existing values or removals (it is not hard to add an explicit check though).

The spending transaction should pay a fee, otherwise, it is unlikely that it would be included in a block. Thus, the funding contract checks that the spending transaction has two outputs (one for itself, another to pay fee), the fee is to be no more than a certain limit (just one nanoErg in our example), and the guarding proposition should e such that only a miner can spend the output (we use just a variable “feeProp” from compilation environment in our example without providing any details). This “feeProp” corresponds to a standard, though not required by protocol.

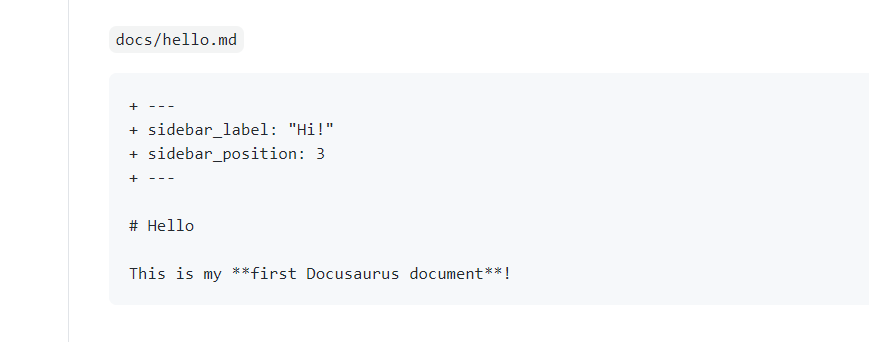

The code below enforces the conditions described above. Please note that the “nextStageScriptHash” environment variable contains hash of the issuance stage serialized script.

val selfIndexIsZero = INPUTS(0).id == SELF.id

val proof = getVar[Coll[Byte]](1).get

val inputsCount = INPUTS.size

val toAdd: Coll[(Coll[Byte], Coll[Byte])] = INPUTS.slice(1, inputsCount).map({ (b: Box) =>

val pk = b.R4[Coll[Byte]].get

val value = longToByteArray(b.value)

(pk, value)

})

val modifiedTree = SELF.R5[AvlTree].get.insert(toAdd, proof).get

val expectedTree = OUTPUTS(0).R5[AvlTree].get

val properTreeModification = modifiedTree == expectedTree

val outputsCount = OUTPUTS.size == 2

val selfOutputCorrect = if(HEIGHT < 2000) {

OUTPUTS(0).propositionBytes == SELF.propositionBytes

} else {

blake2b256(OUTPUTS(0).propositionBytes) == nextStageScriptHash

}

val feeOutputCorrect = (OUTPUTS(1).value <= 1) && (OUTPUTS(1).propositionBytes == feeBytes)

val outputsCorrect = outputsCount && feeOutputCorrect && selfOutputCorrect

selfIndexIsZero && outputsCorrect && properTreeModification

The Issuance Stage

This stage has only one spending transaction to get to the next stage (the withdrawal stage). The spending transactions makes the following modifications. Firstly, the it changes the list of allowed operations on the dictionary from “inserts only” to “removals only”, as the next stage (withdrawal) is only dealing with removing entries from the dictionary.

Secondly, the contract checks that the proper amount of ICO tokens are issued. In Ergo, it is allowed to issue one new kind of token per transaction, and the identifier of the token should be equal to the (unique) identifier of the first input box. The issuance sub-contract checks that a new token has been issued, and the amount of it is equal to the amount of nanoErgs collected by the ICO at till now.

Thirdly, the contract checks that a spending transaction is indeed re-creating the box with the guard script corresponding to the next stage, the withdrawal stage.

Finally, the project should withdraw collected Ergs, and of course, each spending transaction should pay a fee. Thus, the sub-contract checks that the spending transaction has indeed 3 outputs (one each for the project tokens box, the Ergs wirhdrawal box, and the fee box), and that the first output and output is carrying the tokens issued. As we do not specify project money withdrawal details, we require a project signature on the spending transaction.

val openTree = SELF.R5[AvlTree].get

val closedTree = OUTPUTS(0).R5[AvlTree].get

val digestPreserved = openTree.digest == closedTree.digest

val keyLengthPreserved = openTree.keyLength == closedTree.keyLength

val valueLengthPreserved = openTree.valueLengthOpt == closedTree.valueLengthOpt

val treeIsClosed = closedTree.enabledOperations == 4

val tokenId: Coll[Byte] = INPUTS(0).id

val tokensIssued = OUTPUTS(0).tokens(0)._2

val outputsCountCorrect = OUTPUTS.size == 3

val secondOutputNoTokens = OUTPUTS(0).tokens.size == 1 && OUTPUTS(1).tokens.size == 0 && OUTPUTS(2).tokens.size == 0

val correctTokensIssued = SELF.value == tokensIssued

val correctTokenId = OUTPUTS(0).R4[Coll[Byte]].get == tokenId && OUTPUTS(0).tokens(0)._1 == tokenId

val valuePreserved = outputsCountCorrect && secondOutputNoTokens && correctTokensIssued && correctTokenId

val stateChanged = blake2b256(OUTPUTS(0).propositionBytes) == nextStageScriptHash

val treeIsCorrect = digestPreserved && valueLengthPreserved && keyLengthPreserved && treeIsClosed

projectPubKey && treeIsCorrect && valuePreserved && stateChanged

The Withdrawal Stage

At this stage, investors are allowed to withdraw project tokens protected by a predefined guard script (whose hash is stored in the dictionary). Lets say withdraw is done in batches of size N. A withdrawing transaction, thus, has N + 2 outputs, where the first output carrys over the withdrawal sub-contract and balance tokens, the last output pays the fee and the remaining N outputs have guarding scripts and token values according to the dictionary. The contract requires two proofs for the dictionary elements: one proving that values to be withdrawn are indeed in the dictionary, and the second proving that the resulting dictionary does not have the withdrawn values. The sub-contract is below.

val removeProof = getVar[Coll[Byte]](2).get

val lookupProof = getVar[Coll[Byte]](3).get

val withdrawIndexes = getVar[Coll[Int]](4).get

val out0 = OUTPUTS(0)

val tokenId: Coll[Byte] = SELF.R4[Coll[Byte]].get

val withdrawals = withdrawIndexes.map({(idx: Int) =>

val b = OUTPUTS(idx)

if(b.tokens(0)._1 == tokenId) {

(blake2b256(b.propositionBytes), b.tokens(0)._2)

} else {

(blake2b256(b.propositionBytes), 0L)

}

})

val withdrawValues = withdrawals.map({(t: (Coll[Byte], Long)) => t._2})

val withdrawTotal = withdrawValues.fold(0L, { (l1: Long, l2: Long) => l1 + l2 })

val toRemove = withdrawals.map({(t: (Coll[Byte], Long)) => t._1})

val initialTree = SELF.R5[AvlTree].get

val removedValues = initialTree.getMany(toRemove, lookupProof).map({(o: Option[Coll[Byte]]) => byteArrayToLong(o.get)})

val valuesCorrect = removedValues == withdrawValues

val modifiedTree = initialTree.remove(toRemove, removeProof).get

val expectedTree = out0.R5[AvlTree].get

val selfTokensCorrect = SELF.tokens(0)._1 == tokenId

val selfOutTokensAmount = SELF.tokens(0)._2

val soutTokensCorrect = out0.tokens(0)._1 == tokenId

val soutTokensAmount = out0.tokens(0)._2

val tokensPreserved = selfTokensCorrect && soutTokensCorrect && (soutTokensAmount + withdrawTotal == selfOutTokensAmount)

val properTreeModification = modifiedTree == expectedTree

val selfOutputCorrect = out0.propositionBytes == SELF.propositionBytes

properTreeModification && valuesCorrect && selfOutputCorrect && tokensPreserved

Possible Enhancements

Please note that there are many nuances our example contract is ignoring. For example, anyone listening to the blockchain is allowed to execute the contract and construct proper spending transactions during funding and withdrawal stages. In the real-world, additional signature from the project or a trusted arbiter may be used.

Also, there is no self-destruction case considered in the withdrawal contract, so it will live until being destroyed by miners via storage rent mechanism, potentially for decades or even centuries. For the funding stage, it would be reasonable to have an additional input from the project with the value equal to the value of the fee output. And so on.